Heart Age Calculation

Pelank Life ©

Heart age is a simple, easy-to-understand indicator that shows how old your heart is functioning statistically compared to your actual age. If your heart age is higher than your chronological age, it means your risk factors are making your heart age faster than it should.

With this tool, your heart age and 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease are estimated using the validated Framingham (2008) equations. The result is not a medical diagnosis, but it is very useful for awareness and guiding lifestyle changes.

💠 Eligible age range: 30 to 74 years

💠 Required information: sex, age, total cholesterol, HDL, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, diabetes status

💠 If your blood lipid values are in mmol/L, use the unit switch option.

Heart Age Calculator

Estimate your heart age and 10-year CVD risk based on validated equations.

Your Comprehensive Heart Health Assessment

Based on Framingham 10-year CVD model.

What if I change…

Bars show approximate risk reduction if that single factor is optimized.

| Category | Threshold | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Low | <10% (most people) | Low risk |

| Intermediate | 10–20% (needs attention) | Intermediate risk |

| High | >20% (seek medical advice) | High risk |

Detailed Analysis & Recommendations

Your Lifestyle Factors

Your Health Metrics

Disclaimer: This is for informational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice.

About this calculation

This tool uses the Framingham 10-year CVD risk (lipid model, 2008). Heart Age is derived by comparing your profile to an ideal risk profile. Valid for ages 30–74.

- Risk categories: <10% Low, 10–20% Intermediate, >20% High

- LDL, BMI, and family history are not included in the core risk math; they inform advice.

Pelank Life | Body Health Assessment

The Best Body Health Calculators Using Scientific Methods

Developed by Pelank Life ©

Executive Summary

Heart age is a simple, easy-to-understand indicator that shows how old your heart is statistically functioning. If your heart age is higher than your chronological age, it means your risk factors are causing your heart to age faster than it should.

✅ Calculation Model

This tool is based on the validated Framingham 2008 equations (lipid model), one of the most widely recognized models for predicting cardiovascular disease risk worldwide.

❇️ Key Inputs and Outputs

Inputs: age, sex, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure (treated or untreated), smoking status, diabetes.

Outputs: 10-year cardiovascular risk (as a percentage) and calculated “heart age.”

❇️ Who Should Use This Tool?

It is designed for adults aged 30 to 74 in the general population—ideal for those who want to understand their heart health, assess lifestyle changes, or discuss their risk with a doctor.

❇️ Medical Disclaimer

This is an informational and educational tool, not a substitute for medical examination or diagnosis. The results should be considered a general guide, and anyone with high risk or concerning symptoms should consult a physician.

Introduction

What Is Heart Age and Why Does It Matter?

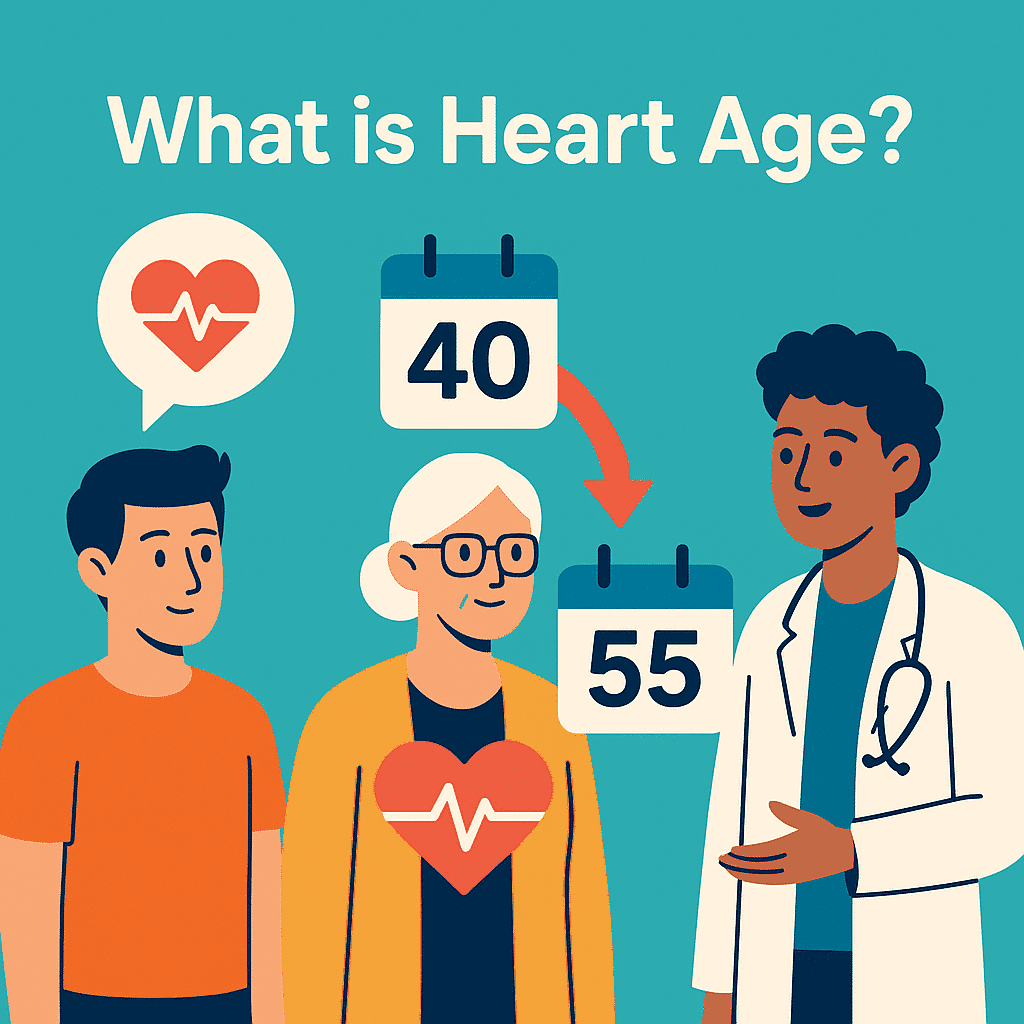

✅ What Is Heart Age?

Heart age is a concept that shows the statistical equivalent of your cardiovascular health in terms of age. Put simply, if a person is 40 years old but their risk factors (such as high cholesterol, high blood pressure, or smoking) resemble those of a 55-year-old, their “heart age” would be estimated at 55. This comparison helps people more easily understand whether their lifestyle and physical condition are making their heart older or younger than their actual age.

🔴 Difference from Chronological Age

Chronological age simply reflects the number of years since a person’s birth, while heart age represents the quality of cardiovascular function based on a combination of risk factors (age, sex, cholesterol, blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking). As a result, two people of the same chronological age can have very different heart ages.

🔴 Connection to Cardiovascular Risk

The higher the heart age compared to actual age, the greater the likelihood of experiencing cardiovascular events such as heart attack or stroke over the next 10 years. That’s why heart age, as a simple and intuitive indicator, bridges the gap between complex statistical calculations and people’s everyday understanding of their health.

🔴 Practical Applications

1️⃣ For Individuals: Provides awareness of heart health and motivation to make positive lifestyle changes such as losing weight, quitting smoking, or controlling blood pressure.

2️⃣ For Doctors or Clinics: A simple, visual tool for explaining risk to patients and encouraging cooperation in prevention and treatment. Instead of abstract percentages, physicians can use the more relatable concept of “heart age” to foster better understanding.

3️⃣ For Health Policymakers: Heart age can be used in population screening programs and public health education as an easy-to-communicate metric for spreading health messages.

Scope and Use Cases

✅ Valid Age Range of the Model

The Framingham model, which underpins the calculation of heart age and 10-year risk, was developed and validated for individuals aged 30 to 74. Therefore, results outside this age range (under 30 or over 74) are not considered accurate and should not be interpreted as definitive. For these groups, the tool should be regarded solely as an educational and awareness-raising resource rather than a reliable risk estimate.

✅ General Population vs. Patients with Existing Conditions

This tool is primarily designed for the general population—people without known cardiovascular disease. For individuals who have already experienced a heart attack or stroke, been diagnosed with heart failure or coronary artery disease, or are receiving specialized treatment, a 10-year risk calculation is not meaningful since they are inherently in a high-risk category. In such cases, proper evaluation should be conducted by a cardiologist or treating physician.

✔️ Individual and Community Use Cases

✅ Individual Use: Anyone can enter their personal data to gain a clearer understanding of their heart health and find motivation to make lifestyle changes.

✅ Community Screening: General practitioners or health centers can use this tool for preliminary screening to identify people at moderate or high risk.

✅ Lifestyle Monitoring: Individuals can recalculate after making lifestyle changes (such as diet or physical activity) to see how their heart age and risk evolve, providing immediate feedback.

❌ Situations Where the Tool Should Not Be Used for Medical Decisions

⛔ To definitively diagnose or rule out cardiovascular disease.

⛔ To determine the need for medication (such as blood pressure drugs or statins) without a clinical assessment by a physician.

⛔ For age groups outside the validated model range (under 30 or over 74 years).

⛔ In special medical contexts such as pregnancy, rare metabolic disorders, or unusual lab values (e.g., HDL higher than total cholesterol).

In summary: this tool serves as an educational and preliminary screening guide, not a substitute for a doctor’s clinical judgment.

Required Data and Precise Definitions

To calculate heart age and 10-year cardiovascular risk, a set of clinical and lifestyle data must be provided. Each of these inputs has a precise definition and a significant impact within the Framingham model:

✅1. Sex

✔️ The Framingham model uses separate coefficients for men and women.

✔️ Men generally face a higher risk of cardiovascular disease at younger ages, but after menopause, this difference narrows for women.

✔️ Therefore, selecting the correct sex is essential for accurate calculation.

✅2. Age (in full years)

The most important non-modifiable factor in risk calculation. In the model, age is entered logarithmically; therefore, each additional year—especially after age 50—has a much greater impact.

✅3. Blood Cholesterol

1️⃣ Total Cholesterol (TC): Higher levels are associated with increased fat deposition in the arteries and elevated risk.

2️⃣ High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL): Known as the “good” cholesterol; higher levels have a protective effect (it carries a negative coefficient in the model).

3️⃣ Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL – optional): Not directly used in the calculations, but highly important for lifestyle and treatment recommendations.

✅ 4. Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP)

1️⃣ Systolic blood pressure (the upper number) is entered into the model.

2️⃣ The model applies two separate coefficients: one for individuals on antihypertensive medication and another for those untreated.

3️⃣ This distinction exists because drug treatment for hypertension is typically initiated when blood pressure is higher or more difficult to control.

✅ 5. Smoking Status

1️⃣ In this model, an “active smoker” is defined as someone who currently smokes (daily or occasionally).

2️⃣ A history of past smoking without current use is counted as “non-smoker.”

3️⃣ Smoking is one of the strongest modifiable risk factors and carries a positive coefficient in risk calculation.

✅ 6. Diabetes Status

1️⃣ Diabetes is entered into the model as a binary variable (yes/no).

2️⃣ A general criterion: physician diagnosis based on fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, or the use of antidiabetic medication.

3️⃣ The presence of diabetes significantly increases risk.

✅ 7. Optional Values (for recommendations and advanced interpretation)

1️⃣ BMI (Body Mass Index): Not used in the Framingham calculations, but highly important in lifestyle analysis and risk-reduction recommendations.

2️⃣ Family history of premature heart disease: If a first-degree relative (father/brother before age 55 or mother/sister before age 65) has had heart disease, the individual’s risk is higher than what the model alone predicts.

📌 Key Point:

For greater accuracy, all data should come from the most recent blood tests and valid blood pressure measurements. Using outdated or estimated values may lead to incorrect heart age calculations.

Units and Conversions

For accurate calculation of heart age and “10-year risk,” it is essential to record laboratory values and blood pressure in the correct units. Any error in units can lead to unrealistic and misleading results.

✅ 1. Blood lipids (Total Cholesterol and HDL)

Laboratory results may be reported in either mg/dL or mmol/L, depending on the country or laboratory.

✔️For Total Cholesterol (TC) and HDL:

✅ To convert mg/dL → mmol/L: multiply the value by 0.02586.

✅ To convert mmol/L → mg/dL: multiply the value by 38.67.

Index | U.S. Unit | European/International Unit | Conversion Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

Total Cholesterol (TC) | mg/dL | mmol/L | ÷ 38.67 or × 0.02586 |

HDL Cholesterol | mg/dL | mmol/L | ÷ 38.67 or × 0.02586 |

✅ 2. Blood Pressure

✔️ Always reported in millimeters of mercury (mmHg).

✔️Example: a blood pressure of 120/80 means systolic pressure = 120 mmHg.

✔️This unit is universal and has no conversion.

✅ 3. Practical Notes on Recording Units in Tests/Records

✔️ Always check the unit column on your lab report.

✔️ Some laboratories in Iran and the Middle East still report in mg/dL, while in Europe and Australia mmol/L is more common.

✔️ When entering data into the tool, always select the correct unit (a mg/dL ↔ mmol/L switch is available).

✅ 4. Common Unit Errors

✔️ Confusing mmol/L with mg/dL:

Example: if TC = 5.2 mmol/L is mistakenly entered as 5.2 mg/dL, the result will be highly unrealistic and close to zero.

✔️ Entering blood pressure in cmHg or kPa: this error is rare but can appear in some records. Only mmHg is valid in this tool.

✔️ Mixing different units: entering total cholesterol in mmol/L and HDL in mg/dL will produce incorrect results. Always enter both in the same unit.

📌 Quick Reminder:

- Fats: mg/dL or mmol/L (convertible).

- Blood pressure: always mmHg.

Scientific Methodology

✅ Introduction to the Framingham 2008 (Lipid) Model

💠 Historical Background and Purpose of the Model

The Framingham model originates from the well-known longitudinal Framingham Heart Study in the United States, which began in 1948 and has followed multiple generations of participants over several decades. The goal of the Framingham models is to predict the probability of developing cardiovascular disease within a defined period—most commonly 10 years. The 2008 version is among the most up-to-date and validated equations used for risk prediction.

💠 Difference Between the Lipid Version and Other Models

1️⃣ Lipid model: Inputs include total cholesterol and HDL. It provides higher accuracy and is most useful when blood test results are available.

2️⃣ BMI-based model: Uses BMI instead of lipid values and is suitable for quick screening when lab results are not available.

The version used in this tool is the lipid-based model.

✅ Formulas

💠 Definition of L (Linear Predictor)

💠 Explanation of Variables

💠 10-Year Risk Formula

💠Explanation of Parameters

- S₀ → Baseline 10-year survival probability.

- L̄ → Mean linear predictor in the reference population.

- The values of S₀ and L̄ differ for men and women.

✅ Heart Age Calculation

💠 Core Idea:

Instead of calculating risk alone, we can ask: “If someone had an ideal risk profile, what age would their heart appear to be to produce the same risk?”

💠 Default Ideal Profile

1️⃣ TC = 180 mg/dL

2️⃣ HDL = 50 mg/dL

3️⃣ SBP = 125 mmHg

4️⃣ No blood pressure treatment

5️⃣ Non-smoker

6️⃣ No diabetes

💠 Formula:

Heart age is obtained by inverting the logarithmic age term in the L equation while holding the other variables at their ideal levels.

💠 Display Bounds:

The result is shown within 20 to 95 years:

✔️ Below 20 years is not meaningful (even for very healthy individuals).

✔️ Above 95 years is not statistically reliable in the underlying calculations.

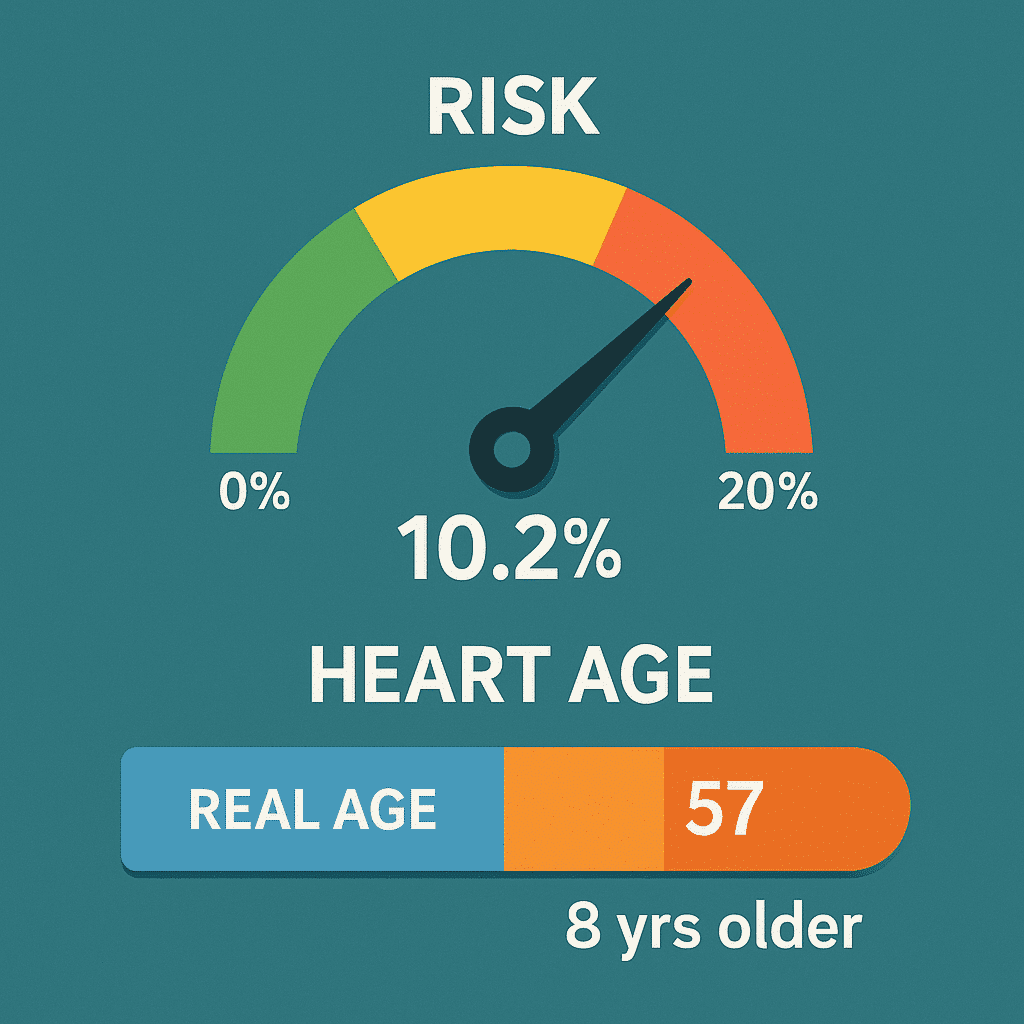

✅ Risk Categories

For easier interpretation, the 10-year risk is divided into three categories:

💠 Low risk: < 10%

💠 Intermediate risk: 10% – 20%

💠 High risk: > 20%

This classification is common in clinical studies and helps both physicians and individuals decide whether lifestyle changes are sufficient or if specialized evaluation and possible medical interventions are needed.

✅ Model Performance

💠 Calibration: The model is well calibrated, based on longitudinal data from thousands of participants in the Framingham study.

💠 Discrimination: The reported AUC falls within the 0.75–0.80 range, indicating strong ability to distinguish high-risk from low-risk individuals.

💠 Limitations: The model was developed using an American population (predominantly white). In other populations (e.g., Asian or African), recalibration may be required for accurate predictions.

Step-by-Step Numerical Examples

In all examples, the formulas and coefficients of the Framingham 2008 Lipid Model are applied. Notation: ln(·) = natural logarithm; S₀ and L̄ (mean-L) are specific to each sex.

✅ Example 1 — Baseline Scenario (Male)

💠 Inputs:

💠 Male coefficients:

💠 Step 1: Calculate LL

💠 Step 2: 10-year Risk

💠 Step 3: Heart Age

(Ideal profile: TC = 180, HDL = 50, SBP = 125, untreated, nonsmoker, no diabetes)

🔴 Result:

✔️ 10-year risk ≈ 10.2% (borderline low–intermediate)

✔️ Heart Age ≈ 57 years (2 years older than actual age)

✅ Example 2 — “Treated” vs. “Untreated” (Male)

💠 Only the SBP coefficient differs.

Untreated (βSBP = 1.93303):

L=24.1955⇒Risk=13.5%L=24.1955 \Rightarrow Risk=\mathbf{13.5\%}L=24.1955⇒Risk=13.5%, HeartAge ≈ 63 years.Treated (βSBP = 1.99881):

L=24.5205⇒Risk=18.2%L=24.5205 \Rightarrow Risk=\mathbf{18.2\%}L=24.5205⇒Risk=18.2%, HeartAge ≈ 70 years.

💠 Explanation: Although systolic pressure is the same, the treated SBP coefficient is slightly larger. In practice, those on treatment usually had higher SBP in the past or more difficult control, so the model estimates a somewhat higher risk for them.

✅ Example 3 — Unit Conversion mmol/L ↔ mg/dL (Male)

💠 Objective: to demonstrate the effect of correct vs. incorrect unit conversion.

💠 Correct conversion to mg/dL (× 38.67):

💠 Incorrect entry as mg/dL (without conversion: TC = 5.2, HDL = 1.3 mg/dL):

🔴 Conclusion:

Mixing up units can make the risk appear unrealistically low. Always check the units on the lab report and convert them correctly.

✅ Example 4 — Diabetes/Smoking Scenario (Female)

💠 Female coefficients:

💠 Step 1: Compute LL

💠 Contributions:

💠 Step 2: 10-year risk

💠 Step 3: Heart Age

Since the display range is capped at 20–95 years, the shown heart age = 95 years.

🔴 Result:

✔️ 10-year risk ≈ 36.3% (very high).

✔️ Heart age displayed = 95 years.

✔️ Key levers for reducing risk: quitting smoking, controlling blood pressure, managing diabetes, and improving lipid profile.

✅ Quick Summary

1️⃣ Heart age and risk values are highly sensitive to key inputs; correct units and whether SBP is treated or untreated are critical.

2️⃣ Differences in coefficients for male/female and treated/untreated SBP can noticeably change the results.

3️⃣ Smoking and diabetes scenarios produce significant jumps in both risk and heart age.

Interpreting Results

✅ Interpreting Heart Age

💠 When Heart Age > Actual Age:

This means the person’s heart is biologically older than their chronological age. In other words, their risk profile resembles that of an older person with an ideal profile.

💠 Practical message: It’s time to intervene—through lifestyle changes (quitting smoking, improving diet, exercising regularly) or, in some cases, medical treatment. Even a 5–10 year increase in heart age can signal a meaningful rise in risk.

💠 When Heart Age ≈ Actual Age or Lower:

This is reassuring—the heart is functioning in line with, or younger than, the person’s actual age.

💠 Practical message: Continue and maintain healthy behaviors such as a balanced diet, blood pressure control, and regular physical activity.

🔴 Caution: Even in this situation, periodic follow-up is necessary, as lifestyle changes can quickly influence results.

✅ Interpreting the 10-Year Risk

The Framingham model estimates the risk of a major cardiovascular event (such as a heart attack or stroke) over the next 10 years.

✔️ Low risk (< 10%):

Probability is low. Main action = maintain a healthy lifestyle. Immediate need for medication is uncommon.

✔️ Intermediate risk (10–20%):

Moderate probability. These individuals should discuss with their physician strengthening behavioral interventions and, in some cases, starting medication (e.g., statins or blood pressure drugs).

✔️ High risk (> 20%):

High likelihood of events. In most cases, lifestyle change must be combined with medical treatment. Regular medical follow-up is essential.

✔️ Borderline zones (8–12% or 18–22%):

In these ranges, it is recommended to use additional assessments—such as coronary calcium scoring (CAC score), stress testing, or extra lab evaluations—to guide more precise decision-making.

✅ Visualizations and Intuitive Understanding

To simplify interpretation, the tool typically presents results with visual graphics:

💠 Semi-circular risk gauge (0–30%):

✔️ Green (0–10%), Yellow (10–20%), Red (>20%).

✔️ A pointer shows the individual’s risk value, making it easy to see their category at a glance.

💠 Heart Age vs. Actual Age bar:

✔️ A dual bar: left side = actual age, right side = heart age.

✔️ The difference δ = (Heart Age – Actual Age) is displayed above.

✔️ Example: “Your heart age is 63 years (8 years older than your actual age).”

These graphical displays help even non-medical users quickly and practically understand their situation.

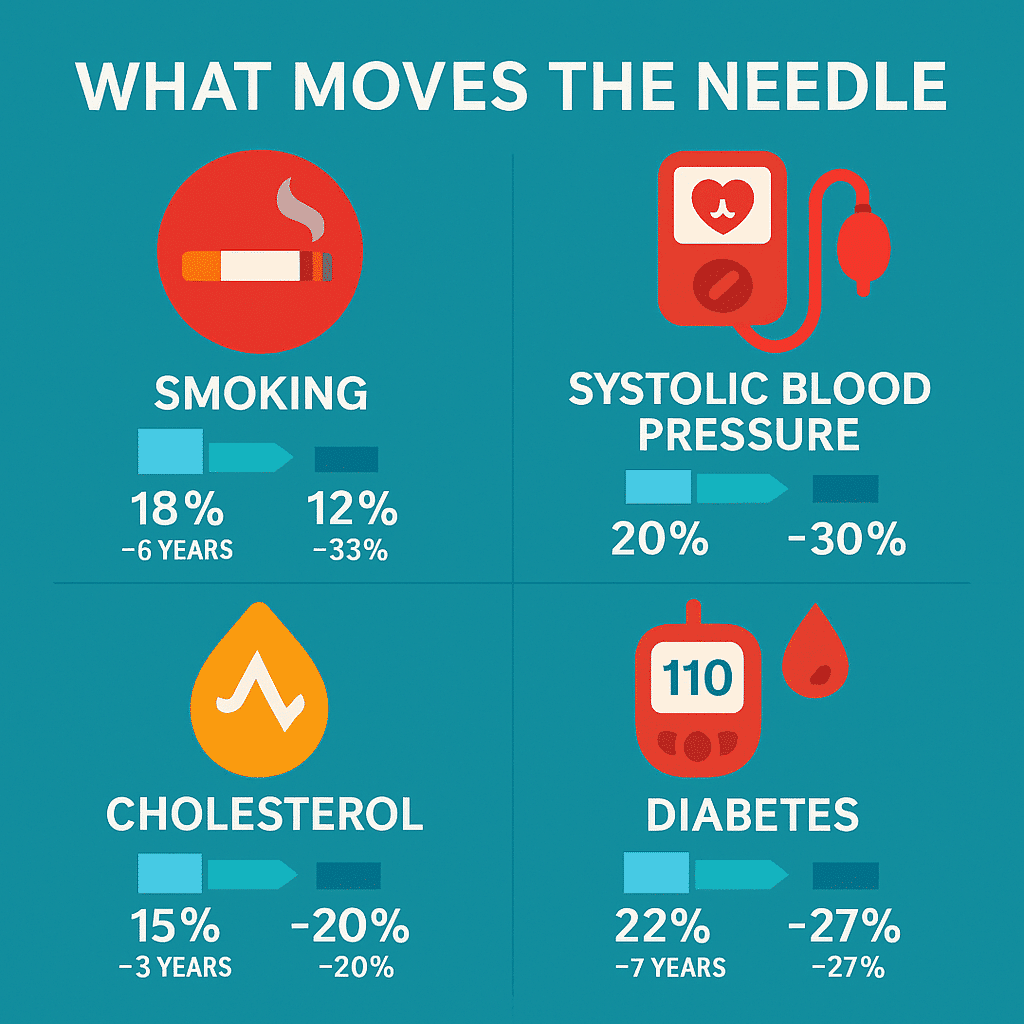

Factors with the Greatest Impact

✅ Smoking

The single most impactful modifiable factor in the Framingham model.

Quitting smoking usually produces the greatest relative risk reduction, since its β coefficient is relatively large and has a multiplicative effect on the overall formula.

For most individuals, quitting smoking can make the heart age 5–10 years younger and cut the 10-year risk by 30–50%.

✅ Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP)

It carries a relatively high coefficient, both in untreated and treated individuals.

Each sustained reduction of about 10 mmHg in SBP → 20–30% risk reduction.

Common clinical targets: <130 mmHg for most people.

✅ Total Cholesterol (TC) and HDL

Rising TC → increased risk.

Rising HDL (“good” cholesterol) → reduced risk.

The effect is somewhat smaller than smoking or SBP, but still clinically meaningful.

Drug therapy (such as statins) and dietary changes can lower 10-year risk by about 15–25%.

✅ Diabetes

Presence of diabetes (especially type 2) → a significant positive effect in the formula.

Tight blood glucose control and adherence to treatment, along with lifestyle changes, can markedly reduce risk.

Diabetes is often clustered with other factors (obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia), so simultaneous management is essential.

📊 What-If Scenarios

Scenario | 10-Year Risk Before | 10-Year Risk After | Relative reduction | Change in heart age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Quitting smoking (55-year-old man, baseline risk 18%) | 18٪ | 12٪ | −33٪ | −6 years |

Reducing SBP from 150→130 mmHg | 20٪ | 14٪ | −30٪ | −5 years |

Reducing TC from 240→200 mg/dL | 15٪ | 12٪ | −20٪ | −3 years |

Increasing HDL from 40→55 mg/dL | 16٪ | 13٪ | −18٪ | −3 years |

Diabetes control (HbA1c at target, medication + lifestyle) | 22% | 16% | -27% | −7 years |

The numbers are approximate (based on the Framingham 2008 – lipid model) and are intended for educational purposes.

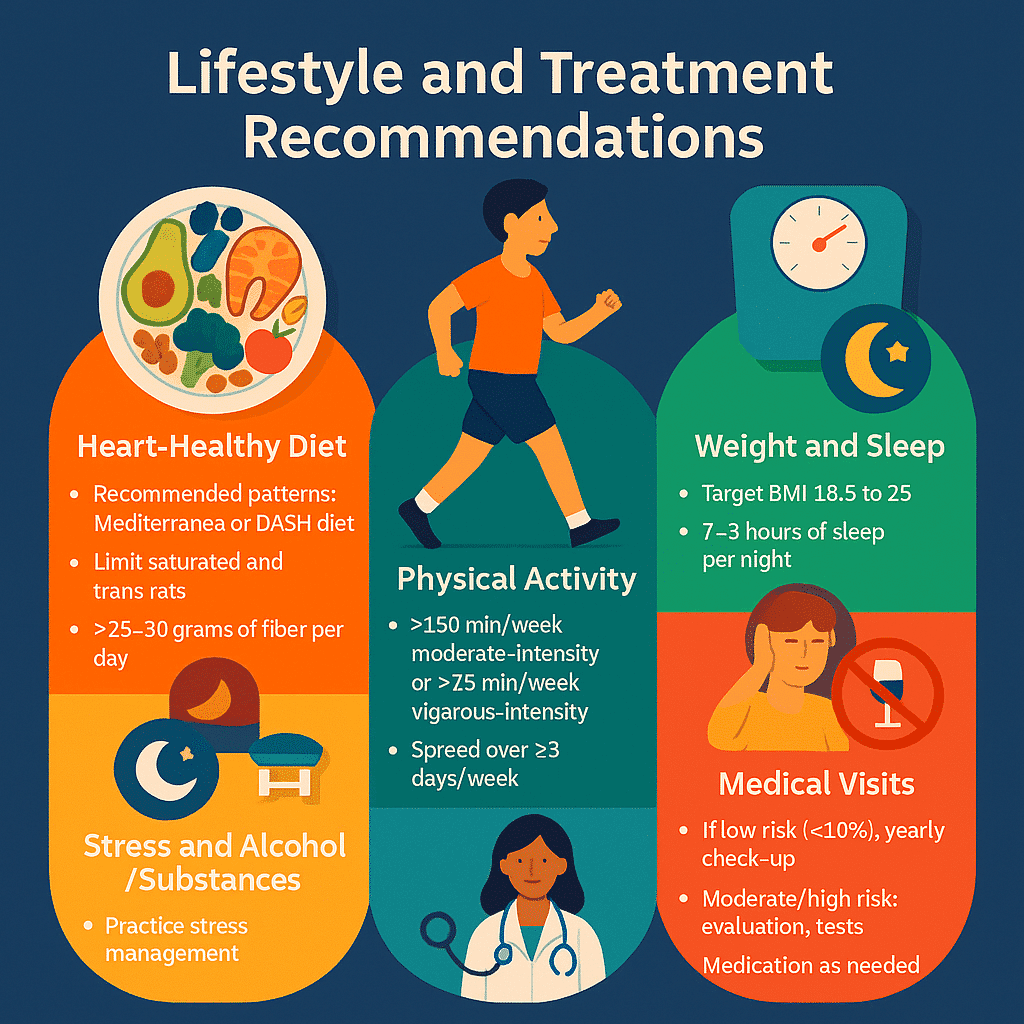

Lifestyle and treatment recommendations

Tiered

✅ Heart-healthy nutrition

💠 Recommended dietary patterns:

Mediterranean or DASH diet (rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and nuts).

Fatty fish (twice a week).

💠 Fats:

Limit saturated fats (fatty meats, full-fat dairy products).

Avoid trans fats (processed foods/fast food).

Replace with healthy oils such as olive and canola.

💠 Fiber:

Aim for at least 25–30 grams of fiber per day from vegetables, fruits, and whole grains.

✅ Physical activity

💠 Intensity and duration:

At least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (brisk walking, leisurely cycling) or 75 minutes of vigorous activity (running, swimming) per week.

💠 Frequency:

Spread across ≥3 days per week, with a minimum of 10 minutes per session.

💠 Safety notes:

Gradual start for sedentary individuals.

Consult a physician for high-risk individuals (risk >20%).

✅ Weight and sleep management

💠 Weight:

Goal: BMI between 18.5 and 25 (or moving closer to that range).

Losing 5–10% of excess weight can significantly reduce cardiovascular risk.

💠 Sleep:

7–9 hours of quality sleep per night.

Sleep disorders (e.g., apnea) should be evaluated and treated.

✅ Stress and substance use management

💠 Stress:

Relaxation techniques (meditation, yoga, deep breathing).

Social support and healthy relationships.

💠 Alcohol:

If consumed, keep to a minimum (ideally zero).

Chronic or heavy use significantly increases cardiovascular risk.

💠 Tobacco and drug use:

Complete cessation of smoking and tobacco.

Avoid stimulants (cocaine, methamphetamine), which greatly increase the risk of heart attack.

✅ Medical follow-up

💠 Low risk (<10%):

Annual check-up and lab tests.

💠 Intermediate risk (10–20%):

Clinical evaluation and discussion of possible medication.

Investigate secondary causes (kidney, thyroid).

💠 High risk (>20%):

Regular follow-up (every 3–6 months).

Multidisciplinary approach needed (primary care, cardiologist, nutritionist, diabetologist).

✅ Pharmacotherapy (general overview)

- Blood pressure: Antihypertensive medications if not controlled through lifestyle changes.

- Lipids: Statins or other cholesterol-lowering drugs for high-risk individuals.

- Diabetes: Oral medications or insulin as needed.

⚠️ Note: These recommendations do not replace medical prescriptions. Medication should only be prescribed by a healthcare provider based on individual circumstances.

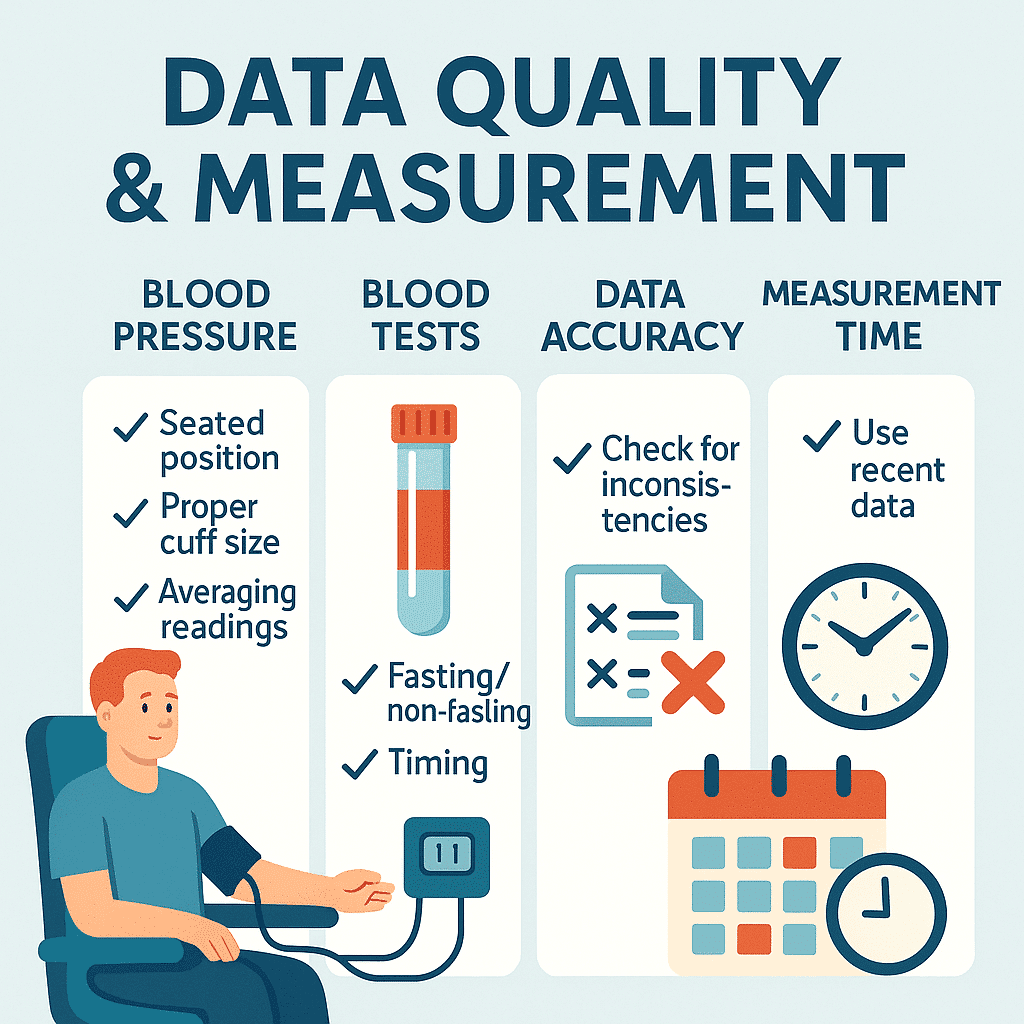

Data quality and measurement methods

✅ Blood Pressure (BP)

1️⃣ Body position: The person should be seated, back supported, feet flat on the floor, and silent during the measurement.

2️⃣ Proper cuff: The cuff size must match the arm size; using one that’s too small or too large distorts results.

3️⃣ Repetition and averaging: Measure at least 2–3 times with 1-minute intervals, and record the average.

4️⃣ Avoiding errors: Measuring over clothing or immediately after exercise, caffeine, or smoking can falsely elevate the reading.

✅ Blood tests (Lipids, Glucose)

1️⃣ Fasting vs. non-fasting: Fasting is not required for total cholesterol and HDL, but is recommended (at least 8 hours) for triglycerides and fasting glucose.

2️⃣ Timing: Morning testing is preferred to minimize the effects of circadian variation.

3️⃣ Accurate sampling: Sample dilution (e.g., due to phlebotomy error) or hemolysis can distort lipid results.

✅ Data accuracy and integrity

💠 Check for inconsistencies:

HDL cannot be higher than total cholesterol (HDL ⩽ TC).

SBP must always be higher than DBP.

Unrealistic values (e.g., TC < 100 mg/dL or SBP < 80 mmHg) are usually due to recording or lab errors.

💠 Use recent data:

Always enter results from the most recent valid exam or lab test.

Older data (e.g., from several years ago) may not reflect significant changes such as the onset of hypertension or diabetes.

📌 Summary

The quality of input data determines the accuracy of the model’s output. Even minor errors in blood pressure measurement or lab units can lead to significantly different estimated risk.

Populations and adjustments

✅ Ages outside the 30–74 range

💠 Reason for limitation: The Framingham 2008 equations were developed and calibrated using data from individuals aged 30–74.

💠 Under 30: Cardiovascular disease is rare, and there’s insufficient data for reliable prediction. In this group, the focus should be on primary prevention and screening for risk factors.

💠 Over 74: Risk patterns change in older adults (especially with chronic conditions), and the model tends to under- or overestimate risk. In these ages, complementary tools or clinical judgment are essential.

✅ Population and ethnic differences

💠 The model was developed using American data, primarily from individuals of European descent.

💠 Studies have shown that in Asian, African, or Middle Eastern populations, the model may not be accurately calibrated and may overestimate or underestimate risk.

🔴 Solution: Use locally adjusted charts or population-specific models when available (e.g., QRISK in the UK, China-PAR in China).

✅ Comorbidities and coexisting conditions

💠 Chronic kidney disease (CKD): An independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease that is not included in the model; as a result, risk is often underestimated in CKD patients.

💠 Endocrine disorders (e.g., hyperthyroidism): Metabolic changes can temporarily alter lipid profiles and blood pressure.

💠 Medications: Certain drugs (corticosteroids, antivirals, psychiatric medications) affect metabolism and blood pressure, but the model does not account for them.

📌 Summary

The Heart Age tool is designed for the general population aged 30–74. Outside this range—or in special situations (pregnancy, serious comorbidities, non-comparable populations)—results should be interpreted with caution and supported by clinical judgment.

Model limitations and disclaimers

✅ Framingham's population origin

The Framingham 2008 model was developed from a longitudinal study in the United States, based on a predominantly white, European-descended population.

As a result, its outcomes may not fully apply to populations with different genetic backgrounds and lifestyles (e.g., Middle Eastern, East Asian, or African populations).

✅ Risk of overestimation or underestimation

Overestimation:

Occurs in populations with lower cardiovascular disease prevalence (e.g., some East Asian communities).

May classify a healthy individual as high-risk.

Underestimation:

Seen in groups with significant independent risk factors (e.g., kidney disease, strong family history, chronic stress, widespread unhealthy diets).

Actual risk may be higher than the model predicts.

✅ Alternative models for different contexts

- QRISK3 (UK): Includes a wider range of variables such as ethnicity, chronic conditions, and socioeconomic deprivation.

- SCORE2 (Europe): Designed for European populations, accounting for regional risk differences.

- Pooled Cohort Equations (USA): Used to estimate ASCVD risk (stroke, MI) based on more recent American data.

- China-PAR (China): A localized model tailored to the Chinese population.

📌 Key disclaimer

The Heart Age tool (Framingham 2008) is an educational and informational resource. Its results are not definitive or sufficient for direct treatment decisions.

Interpretation and action should always be guided by a healthcare provider, based on individual circumstances.

Safety messages and “when to seek care”

🔴 Red flag symptoms

If any of the following occur, immediate medical evaluation or emergency care is necessary:

- Chest pain or pressure (especially if radiating to the left arm, neck, or jaw)

- Unusual or sudden shortness of breath (especially at rest or with minimal activity)

- Syncope or fainting (temporary loss of consciousness)

- Severe or irregular palpitations accompanied by dizziness or weakness

- Sudden leg swelling, rapid weight gain, or extreme fatigue (signs of heart failure)

- Signs of stroke: sudden weakness or numbness on one side of the body, speech difficulties, or blurred vision

⚠️ Thresholds for seeking medical evaluation

Emergency referral (immediate):

- Persistent or severe chest pain

- Stroke symptoms

- Sudden or worsening shortness of breath

Urgent follow-up (within a few days):

- 10-year risk >20% (high-risk), even if asymptomatic

- Very high blood pressure (SBP ≥ 180 mmHg or DBP ≥ 110 mmHg)

- Uncontrolled blood glucose or lipid levels

- Persistent but milder symptoms (frequent palpitations, unusual fatigue, reduced exercise tolerance)

📌 Key safety message

- The “Heart Age” tool is only an early warning signal.

- Actual clinical symptoms always take priority.

- When in doubt → it’s better to consult a doctor or visit the emergency room than to wait.

Privacy and confidentiality

🔹 Minimization of personal data

- Using the tool does not require a name, national ID, or any personally identifiable information.

- Only basic clinical data (age, sex, blood pressure, lipids, diabetes, smoking) is needed.

- This principle aligns with Privacy by Design and GDPR standards.

🔹 Data storage/non-storage in the tool

Proposed policy:

- The tool should process data only within the user’s browser (Client-Side Processing).

- Data should be cleared after leaving the page, with no server-side storage.

If storage is necessary (e.g., for longitudinal tracking):

- It must be done with the user’s informed consent.

- Data must be anonymized or encrypted.

🔹 User security recommendations

- Use the tool on a personal and secure device.

- Avoid entering sensitive information on public computers or unsecured networks.

- If data is stored, use a strong password and enable multi-factor authentication.

- Remember that this tool is for informational purposes only, and data should not be shared elsewhere (e.g., via email or social media).

📌 Key message

The “Heart Age” tool should be designed based on user confidentiality and trust principles:

- Collect only the minimum necessary data.

- No default data storage.

- Full transparency in policies.

User guide for the tool (for the general public)

✅ Step-by-step data entry process

- Select sex and age (30–74 years).

- Enter blood test results: total cholesterol (TC), HDL (and LDL if available).

- Record systolic blood pressure (SBP): indicate whether you are on medication.

- Lifestyle options: smoking and diabetes status (yes/no).

- (Optional) Enter BMI or family history for additional recommendations.

🔹 Unit switch (mg/dL ↔ mmol/L)

In the lipids section, you can change the laboratory unit.

The tool automatically converts values using fixed factors:

- Cholesterol: 1 mmol/L = 38.67 mg/dL

- HDL: 1 mmol/L = 38.67 mg/dL

No manual calculation is needed.

🔹 Viewing results

Display 10-year risk: as a percentage and categorized (low, medium, high).

Show heart age: numerically + comparison with actual age (Δ age).

Graphical display:

- Semi-circle gauge for risk

- Bar comparing heart age and actual age

Print/Download PDF (if enabled): personal results and recommendations can be saved.

🔹 Common error scenarios and solutions

- Entering the wrong unit (mmol/L instead of mg/dL): correct by changing the unit in the menu.

- HDL > TC: recheck lab results (possible entry or lab error).

- Unrealistic SBP (e.g., <80 or >250): verify blood pressure and repeat measurement.

- Age outside the range (under 30 or over 74): model is not valid → display guidance message to consult a doctor.

📌 Key message for the user

The “Heart Age” tool is designed to be simple: a few basic inputs → understandable results → actionable messages.

If an error or ambiguity occurs, warning messages are displayed on the same page.

Quick guide for healthcare professionals

✅ Formula and risk categorization reminder

💠 Linear formula (L):

\beta_{SBP} \; \text{varies depending on} \\ \text{treatment status}

💠 10-year risk formula:

S_{0} \quad \text{and} \quad \overline{L} \\ \text{are defined separately for men and women.}

💠 Risk categories:

<10% → Low

10–20% → Medium

20% → High

✅ Clinical interpretation notes

- The Framingham 2008 (lipid) model is an estimation tool and should not replace clinical judgment.

- In high-risk patients or those with independent risk factors (e.g., CKD or strong family history) → risk may be underestimated.

- In older adults or certain populations → risk may be overestimated.

- Results are best interpreted alongside other indicators (BMI, HbA1c, hs-CRP).

✅ Shared decision-making

💠 Heart age output can be used as a conversation tool between clinician and patient:

- Simple explanation of the difference between actual age and heart age.

- Demonstrate the impact of lifestyle changes (quitting smoking, reducing SBP, improving HDL).

- Help motivate patient adherence to treatment.

- Recommended to use results for documenting shared goals (e.g., lowering SBP to <130 or quitting smoking within the next 6 months).

📌 Key message for healthcare professionals

The Heart Age tool is more than a statistical calculation; it serves as an educational–clinical bridge between clinician and patient.

Frequently Asked Questions

(FAQ)

❓ Is Heart Age accurate?

The “Heart Age” tool is based on the Framingham 2008 statistical model. It can provide a reasonably good estimate but always carries potential error (underestimation or overestimation in certain groups). Its accuracy is comparable to other cardiovascular risk tools but it is not definitive or diagnostic.

❓ What should I do if my lab test was non-fasting?

For total cholesterol (TC) and HDL, fasting is not crucial. However, if triglycerides or blood glucose are also used, a fasting test is recommended. Non-fasting data can provide an initial estimate, but for medical decision-making, the test should be repeated.

❓ Why is my heart age much higher than my actual age?

This usually occurs due to one or more strong risk factors: high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol, diabetes, or smoking. It means your heart functions like that of an older person with higher risk. The takeaway: lifestyle changes and adherence to treatment can help reduce this gap.

❓ What is the difference between mg/dL and mmol/L?

These are two common laboratory units for lipids.

Cholesterol:

1 mmol/L=38.67 mg/dL1 \, mmol/L = 38.67 \, mg/dL1mmol/L=38.67mg/dL

The same conversion factor applies to HDL.

The tool automatically converts units and calculates values.

❓ Is this tool a replacement for a doctor?

No. This tool is purely an educational and informational calculator.

Its results can help you and your doctor in discussion and shared decision-making, but diagnosis, medication prescription, and disease management should only be carried out by a healthcare professional.

Glossary

🔹 Heart Age :

An estimate of “biological heart age” based on risk factors (blood pressure, lipids, diabetes, smoking); a comparison between actual age and cardiovascular risk.

🔹 CVD (Cardiovascular Disease):

A general term for heart and blood vessel diseases, including myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and heart failure.

🔹 SBP (Systolic Blood Pressure):

Systolic blood pressure – the highest pressure in the arteries during heart contraction; measured in mmHg.

🔹 HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein):

“Good cholesterol” (HDL); has a protective role, with higher levels associated with lower risk.

🔹 LDL (Low-Density Lipoprotein):

“Bad cholesterol” (LDL); higher levels are associated with increased plaque buildup in arteries and higher CVD risk.

🔹 Baseline Survival (S₀):

Baseline survival probability over a 10-year period for a reference population (without additional risk factors).

🔹 Linear Predictor (L):

Linear combination of variables and coefficients (β) in the model; a raw index that is then used in the risk formula.

🔹 Calibration :

The degree of alignment between the risk predicted by the model and the actual observed risk in the population.

🔹 AUC (Area Under the Curve):

An index of the model’s ability to distinguish between individuals with and without events; an AUC close to 1 indicates high predictive power.

🔹 Risk Categories :

- <10%: Low

- 10–20%: Medium

- 20%: High

🔹 Shared Decision-Making :

A process in which the clinician and patient jointly decide on management and next steps based on data and personal preferences.

References and sources

Recommended bibliography

📌 Primary sources for the Framingham model (2008 – Lipid)

📌 Authoritative cardiovascular prevention guidelines

📌 Systematic reviews on “Heart Age”

- Lopez-Jimenez F, Cortes-Bergoderi M. A call for action: The need for a national heart age awareness campaign. Preventive Cardiology. 2010;13(4):181–182.

- Grover SA, Kaouache M, Joseph L, et al. Cardiovascular risk and “heart age.” Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2011;27(6):744–747.

📌 Comparison of models

- Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Brindle P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2099.

- Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report on the Pooled Cohort Equations. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2935–2959.

- SCORE2 Working Group. SCORE2 risk prediction algorithms: new models to estimate 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in Europe. European Heart Journal. 2021;42(25):2439–2454.

📌 Referral guidelines

- APA Style (7th edition): suitable for general educational–scientific articles.

- Vancouver Style: medical/clinical standard, used in health sciences journals.

📍 Recommendation:

- For publishing your reference article, if targeting a general audience → APA is more suitable.

- If publishing in medical journals → Vancouver is preferred.

Mohsen Taheri

November 28, 2025